DB x AI (DB Exclusive, 9.30.24)

Consolidating five short essays in defense of artifactual intelligence.

In archeological terms, an “artifact” is something “of human construction”, or something “shaped by humankind”. Pottery and tools you might see in a museum come readily to mind. Most of the world today is the product of what I call artifactual intelligence - it may sometimes bear the flaws of our shortcomings, but it often showcases the spark of our creativity or the wisdom of our experience.

Our world is entering a transition phase - from predominant reliance on artifactual, organic, intelligence to greater reliance on artificial, synthetic/ computational intelligence. This week, I am releasing five short essays outlining my thoughts on this transition.

Here’s the publishing arc:

I – My Pal HAL

Hollywood has been dreaming up ways for AI to kill us for over fifty years. Let’s take a look at some of my favorites as an appetizer.

II – Disappointment.AI

Underwhelmed with your AI experience? Maybe it matters more whether your AI is disappointed with you.

III – Hallucination.AI

We criticize AI for hallucinating. But what if seeing ghosts is a healthy intellectual habit for humans? What happens if we stop learning how to do so?

IV – Catharsis.AI

Autonomous systems promise speed, scale and efficiency. Are these attributes, or virtues?

V – Artifactual Intelligence

How should artificial and artifactual intelligence co-exist?

I – My Pal HAL (9.4.24)

Hollywood and AI Paranoia

I am a sci-fi junkie, so it’s not hard for me to construct fantasy doomsday scenarios revolving around AI.

In the Stanley Kubrick classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Dave, an astronaut on a space mission to Jupiter, has to confront and destroy HAL (a “Heuristically programmed ALgorithmic computer”). HAL faces conflicting directives: one not to tell the human crew about the true purpose of the mission, and another, to convey accurate information. HAL concludes that by killing the crew, he (it?) doesn’t have to lie to them – and so sets out to do just that.

This idea – of a synthetic intelligence so rational that it becomes dispossessed of humanity – captured the attention of my generation. On a pre-COVID trip to Japan (the land of the robots), I made it a priority to search for Japanese language posters of Hollywood movies. Coincidentally, all of the ones I purchased preview the dangers of artificial sentience. Terminator (1984), features a guerilla fighter sent back from the future to protect the mother of the leader of the human resistance that emerges after AI destroys the world. In Alien (1984), space freighter pilot Ripley is betrayed by the android, Ash (played by Ian “Bilbo Baggins” Holm!), whose programming is to preserve the homicidal xenomorph the crew encounters, even at the expense of human life.

Ridley Scott, who directed Alien, explored the more complicated aspects of our relationship with synthetic intelligence in Blade Runner (1982), adapted from the 1968 novel by Philip K Dick, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Deckard is a “blade runner” who specializes in hunting down synthetic humans called “replicants” - a task complicated when he falls in love with the replicant Rachael, who, due to having implanted memories, is unaware of her own synthetic state of being.

Thanks to such pop culture explorations, it is not hard for many of us to grasp the contemporary critique directed at the potential disruptive and destructive power of AI – thanks, Hollywood. Can we trust our digital servant-guardians? How do we know? Should programming override humanity? Can fair and just decision-making ever be compatible with cold logic? This is great stuff for storytelling - and so it’s no surprise that two of the three top Empire’s Top 50 SciFi Movies of All Time (and also adorn my man cave, below).

As much as these scenarios make for great cinematic fodder, these are not what keeps me up at night. Over the coming weeks, I hope to outline realistic, near-term social transformations that illustrate the potentially unintended consequences of the in-motion transition from artifactual to artificial intelligence – and how they could reshape how we relate to each other, in both good and bad ways.

I hope you will stick around for the discussion.

II – Disappointment.AI (9.11.24)

I truly hope to disappoint you.

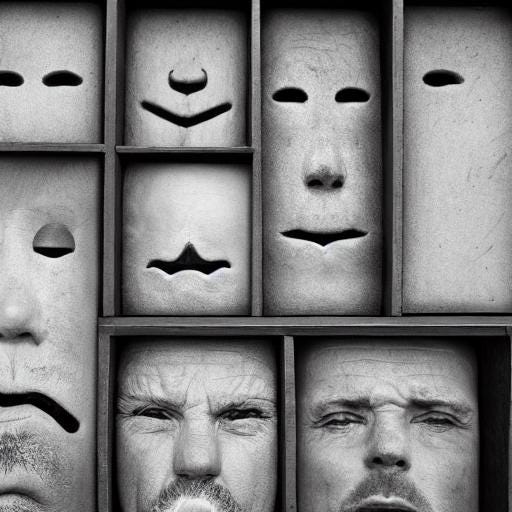

When I used GenAI to create graphics for my SubStack, Deeply Boring, a recurring frustration was images that made no sense. The “multi-faced man” in the lower left of my introductory post “On Poverty and Porosity” is an example. Using the prompt “a drawer divided into compartments with faces in them”, I sought to convey the idea that we put on different faces based on how we choose to show up in separate life spheres. But it kept on generating “heads” that featured multiple mouths and noses. After repeated attempts, I kept the image as an Easter Egg, with a post such as this in mind.

Curiously, I would never have done this with a human artist - to adopt someone’s work with the intent of future public shaming. As a society, we frown upon such trespasses (or used to). An English statute dating to 1843 makes libel punishable by two years in jail. But robots don’t have feelings. Or do they? Microsoft explains that “using polite language [with Microsoft Copilot] sets a tone for the response…when it clocks politeness, it’s more likely to be polite back”.

Interesting. The notion that being polite to AI may invite reciprocal politeness, and is also “good practice for interacting with humans” (Microsoft) seems harmless. But it’s also superficial, because politeness is practiced civility. We all have the ability to be polite, even to people we truly dislike, if we want to. That’s not what matters. The inner voicing and psychological mechanisms of how we truly feel about someone we intensely dislike - and how it influences our behavior - doesn’t happen at the surface level of social etiquette. The outer layer is performance. The inner layer is character. Can (or should) our interactions with AI shape character?

When I interact with people I respect - my parents, teachers, mentors, peers, my children, my spouse - I crave their acceptance and approval. This desire plays a significant role in how I respond to their feedback. If they think my plan is a bad idea, I will revisit my point of view. If they feel I can “do better for myself”, that may encourage me to stretch. But likewise, if they are disappointed with choices I’ve made, I will pause and reflect deeply. The difference in perspective will induce tension and stir up complicated feelings such guilt, conflict, or spite. But it could also shape me for the better. This is how we grow as human beings - through a continual stream of interactions that are both constantly resetting the boundaries of what we want to be and, if we are fortunate, also supplying the courage to strive for them.

But what would happen if we increase our quotient of interaction and dependence on digital helpers that cannot be disappointed in us? After all, it’s not unrealistic to conceive of our children growing up with “access” to the collected wisdom of humanity, delivered on-tap and at scale through synthesized intelligence. LLMs can advise us on career choices, relationships, social graces, professional etiquette, and even questions of moral import (face it, to some people “should I tip my dry cleaner?” isn’t that far removed from “should I break up on TikTok?”). My fear is that the disappearance of disappointment from these interactions changes the means by which the human mind is curated and human character is developed.

We are all familiar with how anonymity has ruined the digital public square - the slippery willingness to say things that we would not say to someone’s face or in the presence of mom. But I think this is merely symptomatic of something bigger. For over fifty years, we have underemphasized the vital role of healthy, loving disapproval as a means of constructive edification. And in so doing, we have surrendered interpersonal accountability for becoming better versions of ourselves. As a species, we risk becoming smarter without becoming wiser. Is this not how we come to find ourselves in a world where swiping on Tinder passes for courtship? They could not be more different. One is brutal reductionism. The other is discovery of self through another.

Another way of stating this is as follows. When we interact with a chatbot, it is an information transaction (“tell me X”). When we interact with a human, it is both an information transaction and a relational interaction (“please spare the time to give me advice…because I trust you”). If we think of these only as information transactions, we may err in treating them as substitutable. But in reality, they are not. If we substitute enough human advisors with digital advisors, two things are lost: first, the relational interaction, and the resulting expectation, motivation and bonding that comes from a life lived together; and second: the ability to practice, improve, observe, emulate, learn, and pass along the skills that bond our lives together.

Am I alone in feeling we desperately need to preserve this marriage of information and relation - delivered through person-to-person conversations at kitchen tables, community centers, and places of worship? I can only disappoint someone who expects better of me. But if there is nobody to be disappointed in me, what is the societal actualization mechanism for my self-improvement? If we let slip away this path to self-improvement, are we better equipped to increase human flourishing in the world?

III – Hallucination.AI (9.18.24)

Seeing is the door to believing.

Part One - Apprenticeship

My older son Ben had his first “serious” internship this year, including performance feedback, a mid term review and 12 hour work days. While I do want him to have a healthy attitude to work and a “Sabbath rhythm” that sets aside time to contemplate, play and rest, I am grateful that some of this time is spent on “grunt work” such as spotting typos and conforming slides to style guides. Why? Because experience has taught me that apprenticeship - learning to do simple things exceptionally well - is commonly a foundation for fruitful creative and critical thinking.

In the 2011 documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, sushi master Jiro Ono explains that he makes his apprentices squeeze boiling hot towels with their bare hands to develop sensitivity and feel before they are even permitted to touch fish. I had my own “Jiro” experience in law school. A well-known law tutor taught (and wrote the book on) a subject called “Conflicts of Laws”. Conflicts jurisprudence sits at a level of abstraction that - when one is asked to write an essay - cries out for the undo, copy and paste functions of a modern word processor. Not for John Collier. Hand-written essays only.

“To force you to think.”

Annoying as this rule was, JC had a point. Tasks, especially simple tasks, can be done mindlessly, or they can be done in such a way as to impart useful disciplines. Writing conflicts essays by hand, I did much more up-front planning. I paused to more carefully consider how to deliver information so a reader is receptive, how to structure an argument to be persuasive, how to choose words for effect, and how to formulate tangible takeaways. Writing by hand, you need to have thought things through to the point that you know where you will land before you can even start. Such skills are helpful for lawyers - but are also relevant whether you are writing a speech for FDR to rally a nation at war, or writing your best friend a birthday card. And though I only draft digitally nowadays, those disciplines have stayed with me and I frequently draw on them when I write for Deeply Boring.

Technology - as John Collier observed - affords convenience, but at the expense of a kind of learning that takes place at a more subliminal level. I fear AI will hyper-accelerate that trend. 30 years ago I learned how to use a Mac to write essays (but not for Conflicts!), and it already risked impairing my thinking. Today, my son Ben uses coding copilots to debug his Python scripts and PANDAS to crunch data - and I wonder what Collier would say. Tomorrow we will rely on GenAI to do our reading, writing and some (or even much) of our thinking. Is this unreservedly good - given we might learn a lot through the playful experimentation that emerges from doing simple tasks, like editing college essays and making sushi?

It seems to me - when starting out at the entry level of a new endeavor - that simplicity directs our creativity and inquisitiveness inwards, the peripheral boredom pressurizing it into an explosive force. In “Jiro Dreams” we learn how Jiro experiments with whether massaging octopus for 45 minutes rather than 30 better brings out the flavor. How many hours of mollusk massage does one clock when scaling the heights to sushi nirvana? Could one still reach the summit without? If you need more persuading: try this.

Perhaps to many of us such effort might seem pointless. But the counterargument might be that perhaps our failure to grasp this is what makes many of our lives feel pointless.

Part Two - Seeing Ghosts

Often, true authority to criticize something comes from knowing it better than everyone around you - authority which is neither cheap nor quick to come by. Good lawyers succeed in the practice of law by paying close attention and uncovering the questions that nobody else is asking (“Mr Simpson, does the glove fit”?). This is not something taught in law school. It is something learned from scanning and re-scanning what we perceive with a skeptical mind.

To illustrate the formative contribution of repetitive tasks in activating such a skillset, let’s imagine the grunt work assignment is reading and summarizing a series of emails from Steve to Bill, lifelong frenemies. In all of the emails, Steve greets Bill with the same salutation: “Hi Bill.” But in one email, Steve gets right to the point and drops the formality: “Hi.” As humans, we pick up on the change in tone immediately. We are sensitive to it. Does synthetic intelligence catch this? LLMs are good at summarizing what is there - but are they even looking out for what is not there? Because when humans analyze, we do not just look for what is seen, but also what is unseen. We recognize that life often unfolds in the gaps.

How effectively does an LLM’s text summarization capability convey such subtleties - if at all? Does assigning workaday tasks to AI result in missing such potentially important nuances altogether? I wonder what to make of a world in which we make certain tasks so easy that our younger generation essentially spam-clicks its way through foundational learning, and loses the opportunity to acquire the essential critical thinking skills that those tasks would otherwise foster.

Lateral thinking is important for a whole host of reasons, but one that is rarely discussed is how such thinking, as an expression of individual agency, is an antidote to technological conformity. Technology drives us towards standardized, prepackaged experiences. Tweets have character limits. ChatGPT produces block text for us to refine. Insta showcases life without imperfections. But it is in the messiness of the edit that life happens. I moved to Substack to escape the LinkedIn character limit. My essays offer more questions than answers. It is often in the imperfections that I find life’s most profound revelations. In all of this, I express my agency - the agency to question, to create, to challenge.

Interestingly, Large Language Models used for Generative AI also have imaginative capacity. Sometimes you ask for a factual response, and get a made up answer. Researchers call this tendency hallucination, or confabulation. This propensity to state untruths is one of the more frustrating aspects of GenAI - one that that advocates of AI Safety perseverate over.

But maybe GenAI hallucinates because the neural network of an LLM was designed to simulate the human brain, which can both reason, based on fact, and speculate, based on conjecture. We “hallucinate” (“see things”) whenever we speculate about the unknown, whenever we ask a question that we do not know the answer to. Without this speculative instinct, we can neither innovate (Could we make all the information in the world indexable? - Brin and Page, 1998) nor challenge the status quo (What would happen if I sent Henry to China? - Nixon, 1971).

Viewed this way, our propensity to speculate is inseparable from our agency, as expressed in critical thinking. We need to imagine, if we are to reimagine the world. If so, perhaps hallucination is nothing more than ChatGPT attempting - but failing - to engage in critical thinking. What should we make of this? Is it evidence of singularity? I think no - at least not yet. An important difference between machine and human hallucination is that when AI hallucinates, it presents falsity as truth. It does not realize it is imagining things (Can AI even understand what it is to imagine? Does it dream of electric sheep)?

But not us. Unlike AI, we are constantly flitting back and forth between reality and fantasy. We can get caught up in the fantasy world of a Lord of the Rings re-run on TV, parallel process the background noise of our children playing (or arguing, or fighting), and ask ourselves whether we want our children to be more like Frodo or Samwise when they grow up, all at the same time. We distrust AI because it sometimes sees ghosts. But we deeply trust each other - to work, live and play together in a world that is simultaneously real/tangible and fantasy/aspirational. The multi-tasking virtuoso that is artifactual intelligence seamlessly interweaves the fantastical suspension of disbelief, rational, logic-based thinking, and the speculative instinct that underlies critical examination.

This is a miraculous trifecta - and whether one realizes it or not, humans have designed foundational experiences to encourage all three in our younglings. We can use play to encourage the first tendency (fantasy), and schooling to promote the second (logic). What a shame if we were to undermine the disciplines of apprenticeship that nurture the third - to abdicate our potential to make miraculous things happen in our pursuit of inconvenience avoidance.

IV – Catharsis.AI (9.25.24)

Why you need to hate me.

In my last two segments, I explored the potential for our growing dependency on artificial intelligence to disrupt the role of interpersonal relationships in fostering personal accountability (Disappointment.AI) and to displace the contribution of small disciplines to the development of critical thinking (Hallucination.AI). In this third segment, I would like to explore how the abandonment of systems that reflect complicated societal tradeoffs could fundamentally weaken the means by which we relate to each other.

My chosen vehicle for doing so is the embattled field of autonomous driving, which has been struggling to get out of the starting blocks. A colleague recently made an astute observation about the path to adoption for self-driving cars. He argued that society will expect a much greater reduction in fatalities from autonomous driving, far below the running average from the analog system we have today, before it would accept such a wholesale change - the marginal benefit must first far exceed the marginal cost. Is this true? After all 63% of U.S. adults do not want to ride in a driverless car. But what could account for this insistence on such a high hurdle for change?

My working thesis is that we intuitively understand that a shift to mandatory fully autonomous driving could irreversibly fray the relational ligature that holds our society together. Let me explain. Today, when we give a teenager car keys and a driver’s license, we are essentially entrusting them with sacred responsibility for human life, whether their own, their passengers’, or those of other road users and pedestrians. Isn’t this a terrifying prospect? Yet we do it millions of times every single day - we, and they, get on the road and interact with dozens, perhaps hundreds, of complete strangers entrusted to act responsibly with their wheeled weapons of destruction. We do this even though some of those strangers may be intoxicated beyond cognition, and despite understanding that unconscious, irrational impulses readily torpedo to the surface as we reflexively judge every driver whose definition of road courtesy fails to comport with ours: slow drivers, tail-gaters, lane-cutters, turn-signal amnesiacs, you name it. Does this not strike you as slightly mad? How could such a system come to be?

The answer is artifactual intelligence. We have somehow, without computers, fabricated a rule system that – despite its bewildering complexity – provides the education, incentives, and disincentives to curb our worst instincts. The rules of property law, tort law (which governs when I negligently drive my car), insurance law, traffic law and criminal law come together to establish rules of engagement for this uncoordinated exercise of point-to-point human transportation. Society has collectively negotiated prescriptions to guide our every exercise of life-preservation responsibilities – whenever you turn that ignition key, you subordinate destiny to these rules, which dictate whether you pay a fine, lose a license, pay a court judgment, or go to jail.

Importantly, all of these interlocking rules are built on a set of relational assumptions. One of the most fundamental of these is that if you do a bad thing, you are responsible, to another human, or to society, for the bad thing you have done. This relational premise is rooted deep within all of us. We are at our core a relational species. We expect others to have certain obligations to us. We expect to have obligations to them. Laws are civilization’s expression of these obligations, and where laws are silent, expectations of morality, etiquette, protocol, custom, and habit weave our lives together into a thrumming hive. This intrinsic relational instinct is the source of our outrage at injustice (a reaction to one human mistreating another in a way outside the relational compact) and of our admiration for heroism (a desire to preserve relational ties of others at the expense of our own interests, and often as an expression of our own relational commitment within the community). Relational instinct is a defining characteristic of our humanity.

Our essentially inter-relational nature is, to me, a key reason why we resist fully mandatory autonomous driving:

We understand, even without having it articulated to us, that a world in which such an arrangement displaces the messy, chaotic artifactual system we have today is one in which when something goes wrong, allocation of blame will not depend on human judgment, but will fall to the cold logic of a computational algorithm.

When the AI decides that the autonomous vehicle your child is driving should stay the course and slam into the rear end of a truck that has slipped on black ice, rather than swerve and endanger the lives of the young family driving in the next lane, justice may be swift - but it may not be very satisfactory.

A responsibility allocation matrix designed by math geniuses will categorize the incident according to the ruleset that deterministically selected human A to live and human B to die - and based on that categorization, a check will arrive in the mail, with the monetary amount for the loss of your child determined by a payout table approved by the administrators of the vehicle autonomy board. If you depend on Medicare, rely on the VA, receive social security, or have visited the DMV - or if you have helped someone who does - you know I am not far from the truth.

If this gives you pause, let me offer three explanations as to why.

Catharsis Externality. In the clunky artifactual system based on laws and incentives, I have someone to blame if things go wrong. The rules are set up for me to get mad at someone - for me to ask the power of the state to intervene on my behalf and hold them accountable. A jury of my peers will hear the evidence of the person who wronged me. They will judge them to be guilty and my pain, while not attenuated, will take one step towards closure. But in the elegant and efficient artificial system, where does this anger go? Can I direct it at the developers who designed the system and instructed it to prefer one life over another? Do I shout at the check that came in the mail? Capturing this “catharsis externality” may be one of the strongest rationales for requiring any such system to clear an abnormally high bar in terms of lives saved relative to the status quo.

Social Reinforcement. The clunky artifactual system is built on the communal repetition of well-understood, clearly-defined, statements of relational expectation. Drive safe. Stay sober. Designate a driver. Teach your kids. Take the keys from dad. You owe it to your fellow citizens to undertake these acts of civic responsibility and collective trust building. But what happens if we remove these signals? In our already fractured and divided society, what is the cost of removing an entire reasonably-well functioning system which has, as a meaningful byproduct, instruction of our youngest members on the virtues of accountability, selflessness, and self-control? What stands-in for the means that make civilization civil?

Trust and Agency. Would you get into the car not knowing if you are human A or human B?

I don’t think we fear self-driving cars in and of themselves. Rather, I think we instinctively resist the dehumanization that can accompany automation.

V – Artifactual Intelligence (9.26.24)

Are we there yet?

The four essays that preceded this one have collectively been a long read, so let’s wrap this up.

I asked three questions:

Disappointment.AI. Can we feel connected and socially indebted to a synthetic intelligence? Can we be successful human beings without the weight of expectation?

Hallucination.AI. Will using synthetic intelligence to perform routine tasks impair the scaffolding process that critical thinking skills are built on?

Catharsis.AI. Will systems dependent on synthetic intelligence displace systems which serve an important secondary function in defining and strengthening social ligature?

I chose these examples to highlight that there is no area of our lives that the AI transition won’t affect - whether our interpersonal growth, our ability to contribute to society, or society’s role in shaping us.

None of this is happening by design. Nobody I have spoken to who is doing AI is trying to blow up the world. They are intelligent, compassionate people. They are trying to solve complex problems, and have admirable track records using cutting-edge technology to do so. None of them wants a world in which we are not challenged to grow, to be intellectually inquisitive, or to communally strengthen our sense of civic responsibility. We all intuitively know that this would be a harsher, more confused, less forgiving, world. So we are all playing for the same team, which is good news.

What is harder to know is what to do about it. “Pause all AI” is neither realistic nor - given the police power a state mandate would entail - democratic. And, as I have recently explained, I believe state-sponsored or institutional solutions are inherently antithetical to desired outcomes for situations such as these.

OK,What Now?

Let’s talk about my AI credentials - or rather my lack of them. As a tech lawyer for an international business, I look at questions related to AI every day, but there are hundreds of thousands of professionals like me doing the same. And while I did test some of these ideas with people doing AI who I respect, I am not a leading voice in AI or philosophy. I don’t have a TED talk or a published paper in the field. So: you may rightly conclude this was a waste of time for both of us - but I hope not.

Here’s my pitch.

I don’t think one needs to be an expert in AI to ask these questions. I think you just need to be interested in people - what makes us work, what makes us better, what makes us whole. On this matter, my primary credential is my painful transparency about my journey. You can read the past year’s writings and judge for yourself if what I speak bears the hallmarks of common sense, wisdom and humanity. If it rings true to you, I hope I have earned the audience of your consideration.

Having raised and discussed these questions in various forums over the past year, I challenged myself to write this out to see if a more complete articulation remained persuasive and compelling. Re-reading my arguments, I remain committed to starting a conversation about this. I am not saying I am right. I am only saying I might be. And I think it’s clear that I am not framing the choice society faces as “do AI” or “don’t do AI”. Rather it’s about “how to do AI right”.

That’s where you come in. You are the most important part of what happens next, and here’s why. I think doing AI right means showing up every day - at work, at home and in our inner selves - in a way that takes time to understand, contemplate, and where appropriate, influence these outcomes. Choosing how to show up is a topic I write about all the time On Deeply Boring. It’s up to each of us to slow the relentless onslaught of reductiveness by insisting that we see each person more completely. It is each individual’s choice whether to pause and evaluate how each interaction over the course of your day can be made more meaningful with a dose of grace. If there is one takeaway I want you to have, it’s this:

An act of giving by synthetic intelligence is programmed performance. An act of giving by artifactual intelligence is sacrifice. There is a difference, and it is one that matters - but only if you care to make it so.

Make It So

On my part, I’m going to keep writing and posting, and to try my best to live out what I believe. Some of my posts get 6,000-8,000 hits, some of them get barely a tenth of that. I have no idea why. It doesn’t matter to me. If it reaches one person, I trust that one person is all it takes to make a difference.

That person could be you.

If something about what I wrote spoke to you, please consider how to further the conversation. Share something I wrote. Share something someone else wrote. Write something yourself. Talk to the people you love about it. Talk to the people you dislike about it. Bring the people you love and the people you dislike together to talk about it.

In all this, may we always be deeply boring; may you have the courage and curiosity to seek to understand what lies beneath the surface; may you be thrilled and overjoyed by the wisdom you find, or by the wisdom that finds you.

This is the gift of the mind we were given. May we each use it to steward the world well.

J

Hi Justin, I hear you on disapproval being a part of that which might help to socialise and give us a healthy sense of right and wrong, however, too many people live under the weight of societal expectations and potential judgement and disapproval — as a somatic coach I see this over and over again, the internalised voice of 'not good enough' and a sense of shame, no matter what they have achieved. Their external persona and inner authentic self are at odds.

What might be more helpful is being able to be attuned to yourself and your needs as well as to those of those around you, this often means transforming your relationship with yourself, and that might mean breaking away from standards and behavioural norms that no longer align with your value system—this can also often mean being willing to be disliked and to disappoint, to both mete out and endure and eventually become resistant (on some level) to disapproval. I believe my parents called it 'developing a thick skin.'

I hear you on AI as well. A friend told me recently that while being with people might be messy and inconvenient, it is worth the discomfort.

While I can agree with that, and firmly believe that human relationships are worth the effort, AI has been able to help propel me forward in ways I don't think a regular human relationship could.

AI is levelling the playing field in many sectors because it can really decrease the knowledge gap between those trained in law and lay people. As a lawyer, you may be skeptical of the ability of these LLMs, but many who previously have had no access to knowledge now have it at their fingertips. Technology is the great leveller.

I have long pondered about the role of AI in our world and what it will eventually mean when they take an embodied form and become indistinguishable from humans. This eventuality is something many have already envisioned. In a bid explore this, I watched 'After Yang' a movie recommended to me by Perplexity. After watching it, it made me reflect more deeply on some key and inescapable themes all humans struggle with, but it was beautiful to see how machines could bring us into a deeper journey therein.

https://medium.com/@Creaturae7/memory-love-loss-and-longing-in-after-yang-8f217b5f37a2