We won the lottery. The time-machine lottery that is. Our ancestors owed fealties to lords, were enslaved as chattel, or were forced into wars for kingdom glory. But we enjoy historically unprecedented choice and control in our lives.

As a child, rather than tilling a field or factory work, I was schooled. My very-white American elementary school teachers did not hold my Asian-ness against me, and put me in an accelerated learning program; my very-not-white Singapore high school teachers did not hold my American-ness against me, and welcomed my opinions, even if they ran counter to orthodoxy.

I was conscripted, but in peacetime. I used that window to reconsider my major, changing it from economics to law. I withdrew from Brown and re-applied to schools in the UK. Before attending Cambridge, I gate-crashed law lectures at the National University. That’s when I met my wife, in a moment of uncharacteristic boldness. After graduating, I declined positions in law practice and the judiciary to clerk for three terms because I loved it; I returned to Harvard as a fellow despite advice to the contrary – a gig which led me to New York.

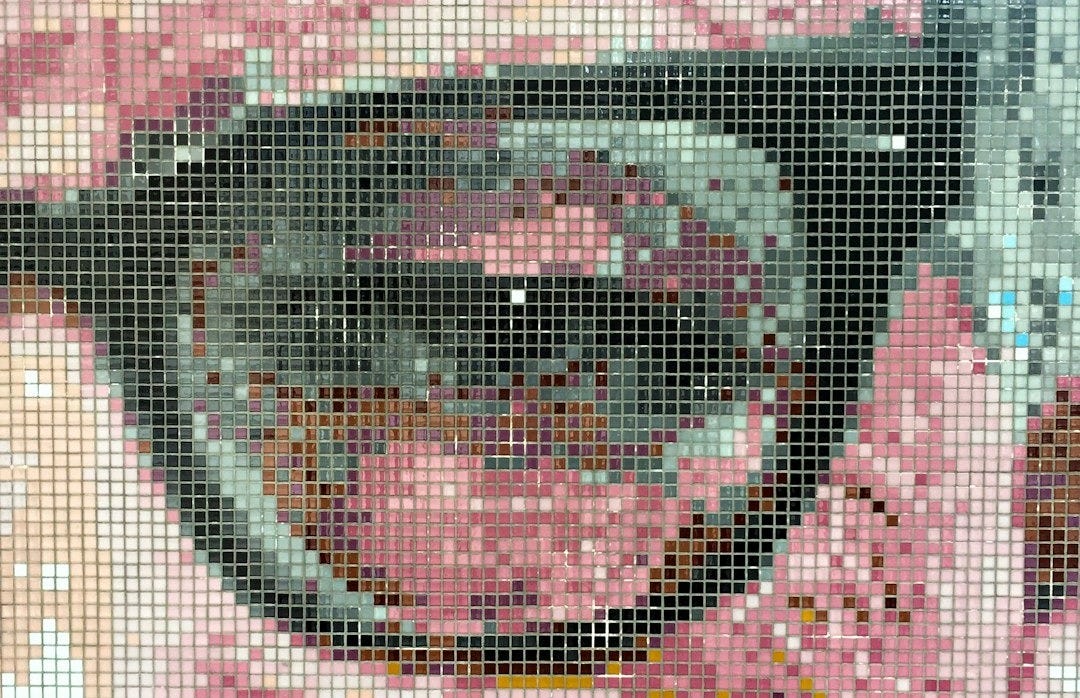

If you reflect on your own life, you can make out a similar mosaic of agency. Yet, as I grow older, I feel more acutely the burdens that flow from my choices: to seek excellence in my chosen profession, to deliver results for my chosen employer, to lead the team I’ve built, to develop the talent I hired, to support and care for the woman I married, to be present to the children I’ve had, to attend to the friends I’ve made, to model values in the community I live in. At the risk of sounding joyless, which I am not, these are burdens (rather than “opportunities”) because the welfare of others is at stake. But my burdens are not are unique. You must feel them too. Do you not?

That such heavy burdens have flowed from such great agency is either an irony or a paradox. An irony, perhaps, to my great-great-grandparents, who lived under far more oppressive circumstances in China. They would have been astounded to learn my story, that such a plant could grow from poor seeds tilled in barren soil. They might be justifiably bemused by my “first world problems”. But perhaps, on closer inspection, they would see parallels indicating that the burdens I feel are but a metastasis of those they themselves carried. Within a narrow prism of limited choices, they strove to bless the generation to come, as do I.

This then, is the paradox of agency. Through agency, we build our lives around our choices. It is “my journey”, “my story”, “my narrative”, “my life”. But emerging from these are “my responsibility”, “my obligation”, “my worry”, and, ultimately, “my burden”.

Is there another way to think about this? Maybe. But let’s talk about that next week.

- J

Justin, this is a beautiful and deeply moving account of your story.

I wish you had not selected the title “Deeply Boring” for this site. Your posts are the opposite of boring, much less deeply boring.

I have not read many of your posts. Perhaps you’ve explained this choice elsewhere?